The New Writing Partnership: How to Make it Work for You

By Susan B. Stroh & Heide P. Boyden *

It’s Saturday night and you’re all alone! You should be writing but who’s going to know if you watch reruns of The Brady Bunch instead. Wouldn’t it be nice to have a relationship like all those other lucky people? You know, a supportive caring significant other. One who will get you through writer’s block. One you can call when you’ve written that flawless poem and want instant feedback. One who doesn’t care that you can’t cook! What you need and want is a writing partner.

Too tired to search? Don’t sweat it. We suggest you ease into a possible writing partnership like you might a love relationship. Date, do things together– and if you know you’ll be good for each other– propose, get hitched and create lively young things!

Choose a Partner

Go ahead, take the plunge! The dating game isn’t all that bad. Ask a prospective writing partner out for coffee. Get a feel for the person’s sense of humor, lifestyle and ambitions. Discover what you like about each other, what you have in common. Do you value each other’s viewpoints? Where is the other person headed? Are you going there too?

It may be a good idea to visit each other’s workplace to determine if you will be compatible. Check out each other’s desk tops, libraries, and writing tools. If the spark has ignited, fan the flames. Read each other’s work. Do you like it? Also (be honest), do you have comparable talent? Are your skills complimentary? Are you both truly committed to succeed as writers? Ultimately, equal commitment is what makes partnerships work. During this courtship, if the answers to these questions are yes, you can plan your future together.

Create the Partnership

Take the time up front, to ask hard core questions, to dig deep and commit the unearthed answers to paper. First, write a purpose for your partnership—call it your mission statement. Why do you both want to write? What effects do you want to create through your writing and your partnership? An example of a purpose might be: Our partnership will allow us to inspire, enlighten and entertain millions of people through writing.

A lofty ambition—yes. But truly, there are no purposes too big. Mutual support and a step-by-step break down will allow you to achieve your purpose. It is for lack of good planning that they are not met. Your purpose should be something you want to write down and tape to your computer to get you through those bleak periods. It should inspire you.

Now that you’ve agreed on the big picture, make a list of all the individual goals that will help you fulfill your purpose. Is your partnership goal to write a book together? Or is it much more long term? Our first goal was to write and market an original screenplay together. Having accomplished that practical goal, we set a broader one: Our writing partnership will effectively facilitate the completion and marketing of many writing projects. Whether writing together or separately, we will support and vigorously help each other make this goal.

In writing purposes and goals, we have three key suggestions:

- Be a visionary: dream big and hone the words of the goal until you can’t wait to get into action.

- Be a pragmatist: be down to earth and honest about estimating effort in achieving any given goal.

- Be a tactician: be willing to figure out all the practical steps you must take to reach your goal.

Now that you know where you want to go, how do you get there? Do you want to complete that memoir that’s been gathering dust for a year? A half million dollars for a screenplay? A Newbery medal? To achieve goals like these, you must map out the territory and then choose the best route to your goal. If you want the Newbery medal, then begin by writing a book for children. Whatever your purpose and goals, choose the paths that will benefit you as well as the partnership, and which will ultimately fulfill your dreams.

Plan Those Babies

By now, you’re in a healthy relationship and have paved the way for making babies—literary ones that is. But it is here, that the analogy falters, because there is no limit to the amount of products you can produce as a writer and they are far less expensive to raise! It may be that all you want to do is write one good suspense novel. Great, then your route is well defined and the structure less demanding. But if you want to write a variety of products, you may find the need to structure your writing life more carefully.

Define the Steps to Success

Whether writing a project together or writing separately, your aim is to help each other complete products efficiently. Most people know how to go about making babies, but sometimes writers don’t. You do it by breaking down any given product into manageable steps and assigning a time for it to be complete. For example, if you want to write and sell a short story, write down each step it takes from getting the idea– right through receiving that check in the mail and seeing your names in print.

Assign each step a deadline. You will not always meet these deadlines, but being accountable to finishing a step by a specified date helps you focus and become more disciplined. (See Sidebar 1.)

Delineate Goals and Roles

Talk about your division of labor up front. Assessing strengths, one partner might choose to do the public relations and marketing and the other research. Will you write separately and fax or email each other pages? Will you meet at a home office? Or will you go away and write intensively at a retreat? Get practical. Do you have all the tools you need to collaborate successfully such as fax machines, compatible software and computer platforms?

Adopt Policies That Help Keep You on Track

You may have skipped the pre-nuptials, but it’s never too late to agree on policies that will allay doubts, fears and future disagreements. Policy can be derived from actions that have already proven successful in your life and that will help you accomplish your goals. Policy regarding the division of money earned, bylines or credits, professionalism and acceptance of assignments outside the partnership, should be hammered out and written down. A policy can be as general as: We will not invalidate each other’s work or disrespect effort. Or it can be as specific as: We will split proceeds 50/50 after expenses for all our collaborative writing ventures.

Meet at a Regular Time Each Week

We have found it helpful to set aside the same time every week to evaluate progress, generate “things to do lists” and to brainstorm ways of removing distractions and obstacles. We also rave about each other’s work and share our accomplishments. The end result of our weekly meeting is a renewed lease on the following week.

Measure Progress

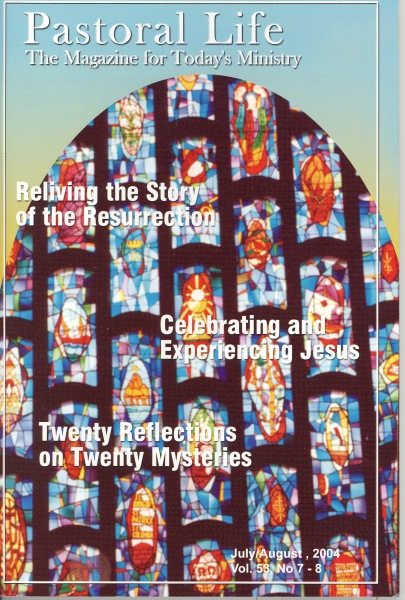

The best way we have found to evaluate progress towards goals is by keeping statistics and graphing them. Statistics are an analytical tool that allows objectivity in determining where more attention or discipline is necessary. Keep track of what you want to increase. When a number goes down, you need to work harder. When a number goes up, so does morale and the closer your partnership gets to achieving goals. Some sample statistics are:

- Number of pages written

- Number of completed products

- Number of products sent to market

- Number of promotional actions completed (from mailing press releases, to book signings)

- Number of people who gave favorable feedback about a product

- Number of paid and published products and

- Gross income from writing. (See sidebar 2.)

If all this structure seems daunting, let us point out how it benefits our partnership. Every year we review our purpose, goals, products and policies. We’ve become bolder in stating our goals and in building manageable steps that help us each gain the experience, know-how and confidence needed to keep fulfilling our writing dreams. We know factually, through statistics, that we have produced ten times more together than we did separately and we are now both published authors.

Deal with Weaknesses and Obstacles

In every relationship, weaknesses and incompatibilities reveal themselves sooner or later and can create problems. Possible problems are disputes over money or credits, lack of organization, procrastination, lack of self-confidence, missed deadlines, different working styles, or distraction from writing due to problems at home.

Before you hot-headedly threaten divorce, talk openly and kindly about the problem. See if you have written a policy that covers this area. Keep an open mind and try not to be defensive. Be willing to confront your own shortcomings and be amenable to change. A supportive partner can help you overcome an obstacle more easily than you might be able to on your own. Maybe all you need is a seminar to learn what it is you’re trying to do.

Oh, and one comment about deadlines. When two partners have agreed upon a completion date, the agreement must be kept. Otherwise, it’s like the husband forgetting to bring home the dry-cleaning when the wife has a high powered meeting the next day! Avoid that kind of friction by delivering what you promise.

Celebrate the Benefits of Partnership

In a partnership, you are supported by someone who wants you to win, who knows your goals as well as you do and ensures every step you take is in that direction. You share everything from writing knowledge and marketing savvy to your favorite battered thesaurus. And by structuring your partnership you will achieve more products in less time.

Whether you choose to author together or independently, you will realize great benefits. If you co-author, your writing will be enhanced by your partner’s fresh viewpoint. Two pens can be better than one. On your solo pieces, your partner can critique and edit your work to perfection with sensitivity, and be there for you when dealing with writer’s block, rejections and difficult clients.

When schedules are tight, one partner can attend a seminar or class and share the knowledge. You can share resources such as books, magazines, guidelines, mailing lists, office equipment and contacts with editors, producers and agents.

Try ghost writing for each other and referring one another to prospective clients. Promote each other and the partnership by authoring press releases and distributing them to your email list. Even write stellar bios and résumés about each other. It’s always easier to blow someone else’s horn than your own!

A writing partnership can be everything you want it to be. Simply structure it to get what you want–to fulfill your dreams. You can write a happy ending, together. You can pop the champagne cork. And if you stick to it, through the highs and lows, you may even celebrate a golden anniversary. Because many will agree, writers get better with age– especially those with a partner.

The End

* Susan B. Stroh and Heide P. Boyden have had a writing partnership for eleven years. As a result of their partnership, they have published several articles, essays, poems, short stories, a children’s book, a biography, and seen their clients publish. They have received short story and screenplay awards.

SIDEBAR 1:

When you have determined your goals and products, break them down into manageable steps. Give each step a deadline, and then check off each completed step with satisfaction.

The Steps to Writing and Selling a Published Short Story:

-Get the idea (to be complete by month/day) √ done

-Write out the themes (by date) √ done

-Outline the story (by date) √ done

-Write the hook (by date)

-Write the opening (by date)

-Write the middle (by date)

-Write the climax (by date)

-Write the conclusion (by date)

-Send to readers (by date)

-Collect feedback (by date)

-Edit and complete final draft (by date)

-Discover the correct market for the piece (by date)

-Write the cover letter (by date)

-Send to appropriate editors (by date)

-Maintain a submission log (by date)

-Sell your story (by date)

-Receive your payment (by date)

-Celebrate your published short story (by date)

SIDEBAR 2:

Graph the statistics you keep.

Here is a graph of the statistic “pages written,” kept on a weekly basis. You may choose to keep this as a daily statistic.

On Writing Biography ~ Ten Hats You Might Have to Wear

By Susan Stroh

Ever wonder what it’s like to write a biography? I wrote one and loved it, then created a niche for myself. The following questions are frequently asked questions.

“Who do you have to be to write biographies?” You might have to be researcher, journalist, organizer, interviewer, counselor, editor, creative non-fiction writer, and archivist and even, upon occasion, photographer. I’ve been called upon to produce the technical elements of a book: handling typesetting, art design, printing and packaging. I also produced an audio book version of the book for one client.

How do you get work as a biographer? My first biography came from Guru.com, an online writers’ resource for jobs. Although I’d never written a book-length biography, I’d published human interest profiles, short employee bios and edited a book-length memoir about a female fire-fighter. From the time I was ten, I had listened to enough strangers tell me their life stories on trains and planes to convince me how easily people talk about themselves. I had interviewed dozens of people on film and video. I thought, how difficult could this be?

After my proposal was accepted, I was asked to give ideas on how to enhance and expand an earlier unpublished manuscript written about the subject (my client’s father). To my critique, I attached a re-written, greatly expanded chapter one. That being approved, the next step was an interview with the client. I competed with two other authors, both of whose bids came in considerably lower than mine. In the evening, I received a call. “Susan Stroh, you’ve got the job and you will soon receive your retainer of $2,000 to start.”

How does one start a biography? The thought that you hold a person’s life in your hands can be intimidating, but I suggest you leap in by doing research: fact-finding, studying resources, time-line development. Look for realities: what happened when, where and under what circumstances. Character and behavior patterns pop out. For your unique take on this individual, isolate what you admire, what captures your attention and revs up your desire to know more.

What are the main tasks in writing a biography? The list includes: research, interviewing, digesting and dissecting transcripts, gathering all primary and secondary source material, writing, editing, polishing, inserting photographs into the text and in the case of corporate work, getting approval along the way. By the way, primary sources include things like the subject’s personal correspondence and diaries, works of art and literature done by the subject, their speeches, any oral histories, audio and video recordings of the subject, photographs and posters, and newspaper ads and stories where the subject is quoted. Secondary sources include other books and articles about the subject, interpretative material such as book or film reviews would be secondary sources.

Once you feel grounded by facts found in your initial research, find out whom to interview. If the subject of your biography is living, do a series of interviews at a time and place that is comfortable for him and that provides you with good recording atmosphere. In other words, don’t interview your subject in his favorite café on Jazz night. It may serve you to videotape your subject, especially if he is elderly or you think a film might be needed sometime in the future to document his views, stories and philosophy. If this is the case, hire a professional crew to light, film and gather the sound. When conducting an audio taped interview, take time checking your recording equipment: batteries, volume and always have plenty of spare fully-charged batteries and two back-up audio recording devices. At the beginning of each tape, record the date, the subject being interviewed, the spelling of the name for the transcriber and where you are interviewing him.

Interview questions should elicit factual, emotional and philosophical answers, and anecdotes about what happened between the subject and key people and events in his life. Feel free to double check the names of places and people, dates, and correct spellings. Your questions should keep the subject interested, so find what he considers captivating, memorable or of interest. Since art includes creating emotional effects on its audiences, look for the affecting components of things with good taste and confidence. You want to create a safe space in which your interviewees feel comfortable recalling and expressing deep-seated feelings and ideas.

Always ask for photos, documents, journals and other materials to accessorize and support the text. Take your time, indulge in the sometimes slow remembrance of things past and create a wonderful rapport with your subject. You’ll learn when to let the interviewees digress and talk about something even more interesting than your question and when to skillfully return them to your line of questioning. One of the great things about interviewing occurs when the subject happens to mention something you’ve never heard and which, it turns out, no one else knew. These are the surprises, the nuggets of gold that suddenly appear while you are digging.

In reviewing the transcripts of interviews, find those pivotal events that launched the subject into one of his purposes in life. I had a handful of sketchy facts about a childhood event especially meaningful to my subject, but could find no one to fill in the details. Sometimes you must use intuition and ingenuity to fill in the cracks where no “facts” can be found—creative non-fiction can be applied. This is different from making something up and passing it off as “fact.”

How do you sift through all the information you gather? Make two copies of your transcripts. Highlight stories, thoughts and quotes that show character and elucidate themes. Cut and paste transcript excerpts and file them into folders according to stages of life, places, people, research topics, title ideas, cover art, back cover copy and so on. Generate a list of pivotal events along a time-line. Start filing materials like newspaper articles, copies of journal entries, photographs and even employment and military records into your chapter or subject files and archival boxes.

How do you know what to include and exclude in a biography? You’ve already asked yourself what is vital, fascinating, captivating and necessary for understanding the subject of your biography. You’ve made some files and boxes of materials according to chapter headings, eras and themes. You’ve organized, indexed, labeled and have handy in archival boxes all the materials you can find. The more you can gather all archival records together before outlining, the better. When you have everything you can find you will be able to outline and structure your book with more authority. The job of selection requires collaboration with the client and often the subject’s family and confidantes. Vision, organization, outlining and approval—those are the steps needed in a legacy biography.

Aside from exciting excerpts culled from the past videotapes taken of my subject, the most engaging anecdotes and fascinating facts came from the interviews I conducted with my subject’s son, wife, employees and family. All of these interviews yielded pay dirt and occasional “dirt” dirt.

A word about “dirt”. Recently, in a class I took on planting vegetables in pots, my instructor clearly differentiated between “dirt” and “soil.” The first is lifeless; the second teems with insects, bacteria and other things which turn dirt into viable soil. As a writer, I grew my book on the soil of life-sustaining stories and heartfelt memories of a man who enhanced the lives of thousands. I left the “dirt” strictly alone and not a speck found its way into my book. I was hired in part because my orientation both to life and to writing is to celebrate what is right with people—that philosophy proving valuable for a commemorative book. My criterion for inclusion of negative things in a biography is: if the subject admits his wrongs, has learned from his mistakes and divulges this in an interview or journal, I would consider including it if it clarified some aspect of his life.

How long did it take you to write the book? After the outline was approved, I wrote for about four months after which I searched through more boxes of memorabilia, photograph albums that had been unearthed while I was writing and editing. This went quickly when I kept in mind the purpose of each chapter, reviewed the themes I wanted to get across and the stories and passages that demonstrated these. I gave each chapter a lead: a juicy tidbit from an interview, a recounting of a dangerous or suspenseful occurrence, a good quotation, even a humorous bit of banter. Anyone interested in writing biography should read several biographies and books about biography by biographers! I did and it helped. Most biographies structure their books around a chronology of events, but other structures can be evolved. Study the table of contents of biographies to get ideas.

What benefits did you get from writing biography? Writing biography expanded my worldview, knowledge, skills and my sense of responsibility towards community. I formed a team of professionals whose expertise contributed to the high quality product we delivered. After the book was published, the client asked me to produce, write and direct a DVD about his father. My team consists of a typesetter, designer, audio engineer, proof reader, transcriber, printer, a CD and DVD duplicating house and a film and video production company.

What part of writing biography do you like best? I like practicing the skill of being the person about whom I write. Being able to step into his or her shoes is fun! By “being” I mean taking the subject’s points of view, empathizing with her feelings, thoughts and vision—thinking what she thinks, imagining what she imagines. A biographer has to become bigger than self to wrap his wits around the enormity and complexity of another human being—to embrace essence. Sometimes being another person requires a leap of faith. You, as biographer, might say to yourself, “I am a great inventor” or “I am a brilliant scientist” or “I am a world famous singer” even if you can’t change a printer cartridge, remember if frogs come from tadpoles, or carry a tune.

While I was writing about an inventor/entrepreneur, I discovered what it is like to be an inventor—to think like one, to be constantly on the lookout for something to make life simpler or easier or more efficient. I write biographies because people’s lives, motivations, deeds and stories fascinate me and I want to celebrate them, their accomplishments and contributions. I feel I am entrusted to tell the best about a life, not as a “puff” piece, exaggerating positive traits, but as a concatenation of true stories revealing character and one person’s journey mastering life.

How to Conjure up Ideas in 10 Easy Steps

By Heide P. Boyden and Susan B. Stroh

Tired of snapping pencils in half and playing computer solitaire while waiting for your muse? And when she finally does make an appearance do her ideas stink? Or are they so impractical that you can’t turn them into anything that would sell in the next millennium? Here’s our advice, writer to writer. Give your muse a vacation and do a little magical inspiring of your own. All you need are your sorcerer’s tools: a pencil (your wand), a notebook and a wee bit of time. We promise that our technique for conjuring ideas that you’ll want to write is easier than pulling a rabbit out of a hat and much more useful.

But let’s start with the basics. Crack open your dictionary and look up the word “idea.” Get a clear understanding of what an idea is to you. We like this definition from Webster’s Ninth New Collegiate Dictionary because it shows action: What exists in the mind as a representation (as of something comprehended) or as a formulation (as a plan.)

To loosen up your creative muscles write your own definition of the word idea. As writers we’ve come up with this: an idea is a thought, feeling or occurrence that can be written and communicated to an audience.

Now that you know exactly what an idea is, it’s time to conjure them up and brew your next saleable writing project. Here’s how:

Step #1: Think of and write down in your notebook, the titles of ten movies you absolutely love—films that moved you, changed you and made you say, “I wish I had written that!” (If you have trouble recalling titles of your favorite films and books, you may want to complete steps #1-#4 at your local library or book store.)

Step #2: Write down the titles of your ten all-time favorite books. If writing something that sells “big-time” appeals to you, stick with best sellers or classics. On the other hand, don’t be driven solely by commercialism. Allow your heart and intellect to guide you in this search for what truly excites you.

Step #3: Write down the titles of your ten favorite children’s books.

Step #4: Write down the names of ten magazines that you can’t wait to read. What’s your first choice from the stack in the dentist’s office waiting room?

Step #5: Study your lists. What do the movies you’ve noted have in common? Are they comedies? Do they have action? Are they quirky? What are their themes? What impact did each movie have on you? Make a list of these common points and then do the same for the top ten books, children’s books and magazines that you like. Now compare your lists. Underline words or concepts that come up more than once. (See sidebar.) These words are the clues as to what type of literature and entertainment you enjoy. For example if the words you underline boil down to humor, history, fantasy, action, and morals you may write a summary statement such as: I like funny, action-packed, up-lifting stories with strong characters placed in a historical or fantasy setting. Or maybe your summary will read something like: I am inspired by strong characters that overcome huge odds to discover or rediscover love and integrity. If you like to be entertained and moved by this type of story, chances are you will also like writing this type of story.

Step #6: Take fifteen minutes and brainstorm ideas based on the summary statement concluded from step #5. For example, using the summary created in step #5, think of a historical or fantasy story that is funny, action-packed, with strong characters and a moral. Your idea doesn’t have to encompass all of these points, but a majority of them. One idea might be: Two fourth graders, a boy and a girl who do not get along, bungle their science project and end up switching bodies. He must live life as a girl and she as a boy until they can cooperate and undo their experiment.

When brainstorming ideas, draw from your life, your experience or what you want to experience and conjure up as many ideas as you can. Write all of them down. Caution! A hex on those who think a particular idea is worthless. There are no bad ideas—at this point.

Step #7: Repeat step #6 two more times. Don’t lose heart and decide that you can’t think of one more idea. Use your intuition, imagination, education and life experience to formulate ideas with wild abandon—no judgment, no censorship. You’re head magician here, make those nebulous ideas materialize, take shape and then capture them on paper.

Step #8: Read through your list of ideas and select your three favorites. Flesh out each. Who is the protagonist? What’s the setting? Is there a hook? What’s the theme? Jot down these thoughts, dedicating a page for each in your notebook.

Step #9: Read through your expanded ideas and assign each the genre that suits it best. Is your idea a good screenplay? Is it a short story? A poem? You decide. Note that assigning your idea a genre is just a starting point. Who knows? It may begin life as a poem and turn into a novel.

Step #10: Choose your favorite idea, the one you can’t wait to write, the one that is completely yours—original and unique. Now take that brilliant idea and write and edit it until it is contained in one clear, concise sentence. Yes, one sentence. This charmed sentence should include the genre and purpose of the piece. Here’s an example: “How to Conjure up Ideas in 10 Easy Steps” is an article that provides writers with a simple process in which to come up with at least one marketable idea they can’t wait to write. Another magical idea might be: “Fitting In” is a comedic movie about a beautiful female celebrity who moves to a remote Alaskan town in order to be anonymous and discovers that she must now cope with the trials and tribulations of being a regular kind of gal.

And that’s all there is to it! If you have completed steps one through ten you are now in possession of a bewitching idea that is all yours. It may be so spellbinding that you’re itching to write, package and send it out into the world. Trust us, this is no illusion, you now have in your bag of tricks, the magic necessary to forever more conjure up captivating and capitalizing ideas.

Sidebar:

Step #5:

1. List the common features for each category (movie, book, children’s book and magazine) and underline repeated concepts. For example:

- Common features in movies: humor, period pieces, action, quirky, fantasy, good conquers evil

- Common features in books: historical, fantasy, horror, strong protagonists

- Common features in children’s books: poetic, moral, action, heartwarming, fantasy, humor, the good guy wins

- Common features in magazines: how-to, pictures, good old-fashioned values, people profiles

2. Write a summary statement incorporating the common traits: I like funny, action-packed, up-lifting stories with strong characters placed in a historical or fantasy setting.

3. Now go to Step #6 and use this summary statement as the basis for brainstorming bewitching ideas.